THE UNIVERSITY BOOKMAN, October 2025

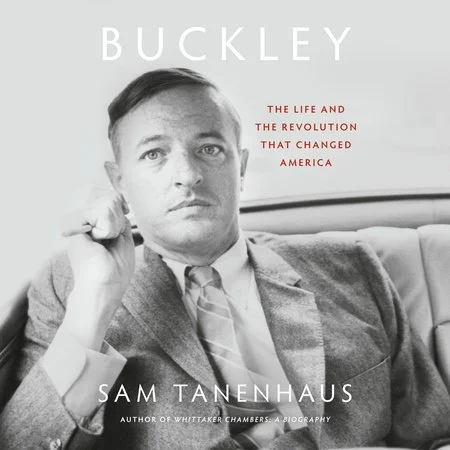

A review of “Buckley: The Life and the Revolution That Changed America,“ by Sam Tanenhaus

Less than a mile separates the Catholic cemetery of Saint Bernard, the burial site of William F. Buckley Jr., off Sharon Valley Road, from the heights of the old Sharon Burial Ground. Yet the distance could not be more pronounced. The geography of this northwest corner of Connecticut explains much of the social and spiritual counter-insurgency that defined this father of modern American conservatism. Buckley: The Life and the Revolution That Changed America, the long-awaited biography by Sam Tanenhaus, does compelling work here in Sharon, in its early chapters describing Buckley’s large Catholic family engaged in its own forms of guerrilla warfare against the town’s Protestant establishment.

Despite the appearances of old wealth, the Buckleys were upstart outsiders. The patriarch William Frank Buckley Sr. (Will, as opposed to his namesake Bill) was the son of a Texas sheriff who gambled big on foreign oil exploration. After losing their homestead in Mexico to a leftist insurrection, the Buckleys decamped to New York, where Bill was born, and then to Sharon’s Taconic highlands by way of Paris and London.

Settling into an estate off South Main Street that he named Great Elm, Will and his wife Aloise just about reached the physical heights of town, but the working-class Irish who inhabited Sharon Valley remained their spiritual kin. In the eighteenth century, the valley’s Webatuck Creek powered the first Sharon mills. A century later, iron production came to the valley along with the laborers to work its kilns. When the Buckleys arrived in 1923, they “worshiped in pews alongside the descendants of Sharon’s working class,” as Tanenhaus writes, “who in earlier times had been drawn to the Northwest Corner by jobs in its iron industry.”

Today the Buckleys are mostly gone from Great Elm. The estate was subdivided and sold over the years after Will’s death, along with his diminishing financial legacy. The family’s unassuming plot in the back of Saint Bernard is what remains of their eternal presence. Will and Aloise are depicted on a central memorial stone as the roots of an elm. Markers of their ten children, including the sister Mary Ann who died two days after birth, are the fallen leaves surrounding them. Only here do we find the flat headstone of William F. Buckley Jr and his wife, Patricia. Christopher Buckley, their satirist son and only child, still much alive, has already added his own marker to the assembly. His epitaph reads: “TOMB IT MAY CONCERN.”

Isolationist, Anglophobic, and anti-Progressive, Will and Aloise were the family’s conservative font. Aloise, from New Orleans, who maintained a winter home with Will in Camden, South Carolina, presented a confederate spirit. Will was a man who “worshiped three earthly things: learning, beauty, and his family,” as Buckley said of his father. He was also a Texas gambler, one who was burned in a game newly rigged by Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Roosevelt, and their class of managerial Protestant elite. Tutored by contrast in the contrapuntalism of Bach, raised as a family in semi-seclusion, several of his children became involved in conservative journalism and politics: Pricilla as managing editor of her brother’s National Review; James as United States senator on the New York Conservative Party line and federal judge; Patricia as a founder of the Catholic magazine Triumph and spouse to Brent Bozell, who was Bill’s Yale co-conspirator, co-author of the book McCarthy and his Enemies, and ghostwriter of Barry Goldwater’s Conscience of a Conservative.

Across his 1040 pages, Tanenhaus is exhaustive and exhausting as the many bodies in Buckley’s orbit get their due. The chapter on the creation of the 1960 Sharon Statement of conservative principles by a hundred Young Americans for Freedom members convened by Buckley for the weekend at Great Elm is especially compelling. The YAF member who collected the notes and typed them up through the night back in her room at the Hotchkiss Inn was Annette Courtemanche, a sophomore at Molloy University. Four years later, she became Mrs. Russell Kirk.

Albert Jay Nock, Willmoore Kendall, James Burnham, Whittaker Chambers, and Frank Meyer each exerted their own gravitational pull on Buckley’s trajectory as the conservative isolationism of America First gave way to Cold War anti-Communism. Founded in 1955, Buckley’s National Review meanwhile mentored a generation of younger writers, including no less than Arlene Croce, Joan Didion, John Leonard, Renata Adler, Garry Wills, Hugh Kenner, and Guy Davenport. An undergraduate Betty Friedan (née Goldstein) makes a cameo as the Buckley sisters’ protector at Smith. At the same time, a nineteen-year-old Sylvia Plath appears at Maureen Buckley’s debutante ball at Great Elm.

Readers of this book may have differing opinions about where its narrative turns against its subject. In the endless section on civil rights, there are hints that Tanenhaus intends to burden Buckley in his missteps, distractions, and peccadilloes. At a certain point, Tanenhaus seems to turn his focus on everything Buckley should have done but didn’t, such as finishing an ambitious book project titled Revolt Against the Masses rather than attending to his many novels (I was his writing assistant for one of them), columns, and television appearances (and the yearly income he needed to maintain National Review). As he aligns himself with Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger, Buckley, in Tanenhaus’s telling, falls short of his intellectual promise and softens in the trappings of power and prestige.

There is ultimately less “life” here than a focus on the “Revolution That Changed America.” As the chapters roll on, Buckley appears increasingly inert, passive, and surprisingly silent—a reactive presence within unfolding events. A charitable interpretation would be to say that Tanenhaus rejects the “great man” theory of history, that we are merely the sum of historical forces applied to us. In elevating Buckley’s faults over his features, more likely than not, this book is designed to impugn the American conservative movement by diminishing the singular leader who created it.

In any case, by the end, it becomes clear that Tanenhaus never really gets Buckley, no matter how many words he deploys to describe the revolution around him. The long delay in this book’s completion, some twenty-seven years in the making, is just one indication of a biographer who loses the thread of his subject and becomes increasingly indignant as he looks over the remaining stitches.

From the geography of Sharon to the faculty at Yale, Buckley took on an entrenched progressive elite. His greatest achievement was to manifest an alternative American aristocracy, a counter-elite that took full form in the presidency of Ronald Reagan. Buckley was a “Catholic aristocrat of the Spanish persuasion,” as a friend once said. He understood the spiritual dimension that informed America’s social and political dynamics. His famous quip about preferring to be governed by the first 2,000 people in the Boston telephone directory than by the 2,000 people on the faculty of Harvard University was more a slam against the progressive Ivy League than a positive appraisal of the average Bostonian. At the time Buckley attended Yale, the school maintained admissions caps on Jewish and Catholic applicants in equal measure. So when Yale University sent its plenipotentiary, McGeorge Bundy, out to slam God and Man at Yale, Buckley’s 1951 broadside against the school’s progressive professoriate, Bundy centered his attack on Buckley’s Catholicism.

Buckley may have never finished Revolt Against the Masses, his answer to Ortega y Gasset. Instead, life itself, fully lived, became his revolt played out across a multitude of media. From restoring God to “man at Yale” to taking on Godless Communism, Buckley waged a holy war aimed at the highest levels of American society—and he largely won. Nevertheless, Buckley: The Life and the Revolution That Changed America is a tome that proves the progressive elite still exists, and that not everyone has been won over by his revolution that changed America.